Monitoring an Anthrenus (Coleoptera, Dermestidae) infestation: an opportunist ‘Lockdown’ project

Colin A. Howes, 7 Aldcliffe Crescent, Doncaster DN4 9DS

“Lay not up for yourself treasures upon earth

where moth and rust doth corrupt”

Mathew VI, 19.

During the spring of 2020, initially while in quarantine during a suspected covid-19 flu infection and subsequently during the Coronavirus pandemic UK ‘Lockdown’ requirements, I spent most days from about 11am to 7pm working in a south-facing conservatory at the rear of 7 Aldcliffe Crescent, Balby, Doncaster (SK557999).

The conservatory is a brick built construction of 14ft by 6ft with an uncovered concrete floor, plastic roof, white UPVC double glazed windows and door and white UPVC internal windowsills against which insects from 0.1mm were clearly visible. Three dark green plastic plant troughs (2ft 2in. x 8in) containing a range of pot plants and geological objects were arranged on the windowsills and a total of 7ft 6in of wall space was occupied by wooden slatted shelving used to store runs of scientific journals and as temporary accommodation for the store boxes housing the late Albert Henderson’s extensive research archive on the Rabbit and Hare Warrens of Britain and Europe.

Background

The museum beetles Anthrenus verbasci (L.) (Coleoptera, Dermestidae) are somewhat like small ladybirds (Coleoptera, Coccinellidae). However, they are not glossy, their elytra having an attractive matt chequerboard pattern formed by patches of black alternating with reddish-yellow scales.

Larvae popularly known as ‘woolly bears’, are yellowish-brown and hairy, with a tuft of longer erectile hairs at the rear end. They are highly mobile and wander in search of food and pupation sites. The adult beetles emerge in the spring. They fly well, are attracted to light and to flowers where they feed on pollen and nectar.

In the wild eggs are laid in the linings of birds’ nests and other animal nests or in dry carrion, where the larvae can feed on feathers, hair and fragments of flesh.

Where they appear in large numbers in domestic property, sources of infestation are typically a bird’s nest under the eaves, a felt carpet underlay and woolen cloths in a box of cleaning materials. In spite of their varied diet, when they attack textiles, museum beetles usually prefer clean new materials such as fine cashmere sweaters (Mourier & Winding, 1975). They will also feed on dead insects and are much feared by curators of insect collections.

[or even accumulations of dead insects in spider’s webs]

Based on enquiries handled by natural history staff at Doncaster museum, Anthrenus seems to have increased in frequency as a household pest since the 1980s, enquiry frequencies progressively outnumbering those concerning house moths (Lepidoptera, Tineidae).

Methods

Whenever an Anthrenus adult was noticed on any of the bright white window frames or windowsill it was killed and recorded in a project diary.

Results

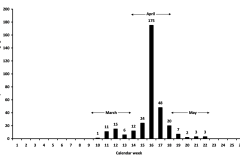

The first adult Anthrenus was encountered on 9 March and the last on 8 June with a total of 328 specimens recorded. The daily emergence numbers ranged from 1 to 48 with a mean of 2.54 in March (n 28), 11.18 in April (n 246), 2.52 in May (n 53) and in June (n 1) . The peak emergence events included 42 emerging on 20 April and 48 on 23 April.

Figure 1: Numbers of beetles emerging per calendar week.

Figure 1 shows the weekly totals of emerging adult beetles and figure 2a compares the daily emergence numbers with the hours of sunshine and maximum temperatures monitored at the nearest weather station.

Discussion

With emergence of adults extending through March, April and May, markedly peaking in mid-April (see figure 1), seasonality broadly greed with that stated in Mourier & Winding (1975).

The source of such a large infestation was something of a puzzle since the conservatory wasn’t used to store clothing, fabric or insect collections. However, the focus of the infestation was indicated by numerous discarded larval/pupal skins and freshly emerged beetles found amongst the debris of insect exoskeletons accumulated in spider’s webs under the plant troughs and behind the storage wracking.

The accommodation is shared with a short-haired dark tortoiseshell cat Felis catus L. whose bowl of dry cat food and a litter tray with mineral cat litter were present throughout the monitoring period. Although there was no evidence of Antrenus associated with contents of either food bowl or litter tray, fine cat food debris falling into some of the open topped store boxes of the Henderson archive certainly attracted larvae or adults indicating this to be a favoured food source. Although the thoroughfare through the conservatory was regularly vacuumed, substantial amounts of moulted cat fur had accumulated amongst the general debris in the spider’s webs behind the wooden wracking and could well have been an additional attraction for the Anthrenus infestation.

Since the adults were strongly attracted to light, not only was it easy to catch them on the south-facing conservatory windows and window sills, none were ever encountered in the adjoining, somewhat gloomier kitchen or elsewhere within the property.

References

Mourier, H. and Winding, O. (1975) Collins Guide to Wildlife in House and Home. Collins, London.